On Saturday 28th March, I was invited to speak at a conference organised by the Reading Reform Foundation (RRF). The purpose of the event was to highlight the vital importance of systematic synthetic phonics (SSP)*. A great variety of speakers with different areas of expertise were asked to talk on the subject and it seemed many fruitful conversations were had by those who attended. I was invited to talk about my decision to use SSP with secondary school students within SEN, which will be available online shortly.

*Simply put:

Systematic Synthetic Phonics (or SSP) is a structured, repetitive approach to teaching reading with a total reliance on the smallest units of explicit sounds – in both spoken form (‘phonemes’) and written form (‘graphemes’) – to teach reading. This method usually starts with the most common sounds and moves through to more complicated ones e.g. knowing a ‘dge’ makes the same sound as a ‘j’, and a ‘tch’ makes the same sound as a ‘ch’.

This is in contrast to analytic phonics, where students are often asked to read beyond a difficult word to the end of the sentence, then attempt to guess it using contextual clues. This approach, while helpful in the opinion of some, does not develop the reading skills of a student nor help them learn explicit sounds, since they have simply guessed the word through their understanding of the rest of the passage. This also often has negative impact for those new to English, since their knowledge of vocabulary at entry point to the UK is minimal, so there are flaws in the reliance of a guessing technique.

While I have been aware of the benefits of using a structured approach to reading for a long time, it has made me more sure than ever that this is the most targetted, reliable, efficient and, without wishing to go overboard, moral way to teach reading.

Unfortunately, official governmental guidance does not stipulate that a single methodical approach to teaching reading is key though does advise this. For me, a directive which would acknowledge the necessity of teaching reading through SSP would be a great step towards ensuring that far more students might have the opportunity to learn to read before they leave primary school.

Not to add fuel to the fire in the debate around the phonics screening check at the end of Year 1, but I am a keen and outed supporter. Ensuring that any individual has a good grasp of the fundamental skills of reading and writing can surely only be a good thing.

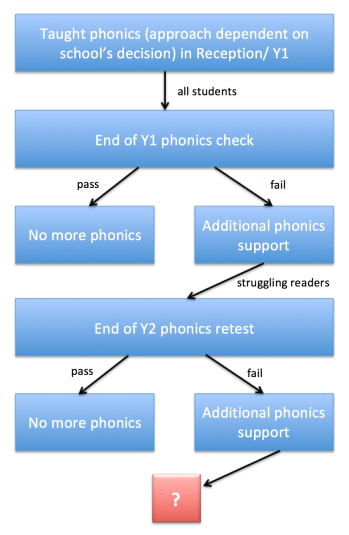

With my SEN head on, however, there seems to be a flaw in the system. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but my understanding of it is as follows:

The DfE website states that:

… And after that? What happens then?

aa

If, as educators, we acknowledge that children physically grow at different rates, mature emotionally at different times and adopt new knowledge at different speeds, is it okay that we let so many fall off the radar beyond Y2 simply because their learning of our complex alphabetic code has not fit into our man-made termly organisation?

There seems to be a black hole for those students who have not grasped reading by this point and, in my opinion, this could be one key factor contributing to the situation I’m faced with as Literacy Leader of a secondary school, welcoming in substantial numbers of students arriving in Y7 who are still unable to read. Pass at Y2 or branded SEN. Hereth begineth the dreaded ‘gap’.

I have no doubt that schools in the majority do their best to scaffold the learning of students who fail to pass the phonics check at Y2. It is our moral obligation to ensure that our learners are equipped as best as possible for the education journey they walk. However, there are questions we need to be asking here:

- What does the research suggest and how are we applying it to our own classrooms?

- If there are so many students failing to grasp reading across the UK, are we really using the most suitable approach that meets the needs of ALL our students?

- How else can we support students beyond this stage if they haven’t learnt it by the end of Y2?

- Have we done all we can to ensure this student is able to access the curriculum?

Disclaimer: I have been a primary school teacher. I have seen the amazing job that primary school teachers do, day in, day out. This post is by no means an attack on the teachers who deliver phonics to younger students. My intention is simply to verbalise my thoughts on the current situation I observe from a secondary perspective and explore ways we might overcome some of the flaws in the system.

If we are to see illiteracy in the UK reduce by any significant measure, we have a duty to ensure that:

- the most targetted, research-based, fail-proof, methodical approach to teaching reading is employed

- ALL students are supported to a point where they are able to read and write independently as early as possible (and beyond!)

By achieving these two points above, I am almost certain that we would see numbers of those arriving at secondary labelled as ‘SEN’ dramatically decrease, since there would have been no gap (or at least a much smaller learning gap) to close. I’m sure we would begin to witness less students arrive at secondary who are clearly able in many areas of the curriculum, extremely competent in verbal responses, but branded with a ‘Specific Learning Difficulty’ in reading. I do acknowledge that there will always be some level of need in this area, which is likely to extend to education in the older years. I do also recognise, however, that we are clearly doing something wrong at present and, until it is addressed and corrected, we are failing a great number of our students.

Hi Josie,

It was great having you speak at the Reading Reform Foundation conference (March 2015) – and it was notable how much interest was generated by your particular talk describing intervention for secondary-aged pupils – more questions raised by the audience than for any other talk on the day! That in itself speaks volumes.

You are right that we should be worried by phonics coming to an end after Year One other than for the Year Two children who did not reach the Year One Phonics Screening Check.This is misguided.

I think your flowchart for the Year One Phonics Check outcomes is excellent as it depicts worrying attitudes and perceptions about phonics teaching and learning. The current scenario in England suggests that any child who has not grasped our extremely complex English alphabetic code by the end of Year One – as demonstrated by reaching or exceeding the benchmark for the Year One Phonics Screening Check – must be ‘special needs’ in phonics, with the implication that phonics provision should not need to continue in Year Two for the children who did reach the benchmark in the phonics check.

This in itself suggests that many people, probably most, have no real idea how very complex our English alphabetic code spelling system is – and that even if children are up and running with their phonics decoding (blending for reading), they will still benefit enormously from a continued emphasis on phonics for spelling (encoding: orally segmenting the sounds all-through-the-spoken-word and then being taught ‘which’ spelling alternative is required for specific words and spelling word banks).

Further, children need alphabetic code knowledge and the blending skill to equip them for lifelong reading of new and unknown words rather than just familiar words. Thus, phonics is required for adult literacy for both reading and spelling – but most adults and children don’t even realise this as it is associated – as we are discussing – with infants and infant teaching. In other words, many of the children who DO reach the phonics check benchmark are likely to need further work on the complex alphabetic code – the check is not that challenging and many children in Reception are capable of doing well on it with high-quality phonics teaching.

This change of perception of phonics from ‘baby stuff’ to ‘adult stuff’ is essential – and surely at the heart of what you are raising in your posting.

I agree that we also need to be looking at the quality of the teaching of phonics itself – and not just assume that children who do not reach or exceed the benchmark of the phonics screening check are special needs and could not have been expected to do well. The year on year results of the phonics check are already showing us that teaching effectiveness can be increased – and since the pilot check in 2011, we have gone from 32% of the children reaching the benchmark to 74% in 2014.

As you know, I created a graphic entitled ‘The Simple View of Schools’ Phonics Provision’ for the RRF conference – to indicate that the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ and even the ‘how long’ of schools’ phonics provision is very different from school to school across England – and we can identify certain patterns of provision as I endeavour to indicate here:

http://www.phonicsinternational.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=847

I think that the whole teaching profession, and the teacher-training profession, should be well-trained in phonics and phonics provision, that the perception of phonics needs to change radically – and phonics needs to be understood as very important for the teaching of English as a new and additional language – regardless of the age of learners.

Keep up the good work!

Debbie

Illiteracy: What are we going to do about it?

We start here with the notion of ‘Alphabetic Code Charts’ to make our truly complex English alphabetic code ‘tangible’. If anyone is interested, I provide a wide range of free, downloadable Alphabetic Code Charts for different users – e.g. teacher-training, classroom charts, mini charts – and so on:

http://alphabeticcodecharts.com/free_charts.html

I’ve posted here about your great piece:

http://phonicsinternational.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=2210#2210

Debbie,

Thanks so much for your response(s) here. I felt really privileged to be a part of such a valuable event organised by the RRF. The more I explore the issue, the more sure I am that SSP is the best route for delivering phonics in order to develop reading across the UK. With such a complex alphabetic code, a reliance on knowing each individual sound is, for me, the only way to fully achieve the status of a ‘free reader’.

Finding ways to inform students/parents/teachers alike that phonics is not a ‘baby’ think but a way to be able to tackle such a beautiful, detailed language is important, I agree.

I have been made aware that the phonics screening check does not yet test all the GPC’s we teach, but a sample 40 or so of them. It seems to me that, while this would help measure ability between peers to some extent, with your expertise, would you advise that we should be assessing knowledge of ALL GPC’s in order to provide a thorough diagnostic test? Or do you feel this isn’t necessary since some aren’t taught all by the end of Y1? Genuinely interested in your thoughts on that.

I will be looking to invest in your resources this half term at our school. Thanks for the links – very useful.

Kind regards,

Josie

I think that teachers should be aware that children can do apparently well in the Year One Phonics Screening Check without a thorough-enough knowledge of a comprehensive range of letter/s-sound correspondences. This will matter for at least some of the children – others may well be able to ‘self-teach’ as they get older. Some, however, will definitely not be able to self-teach. All the children will benefit from phonics for spelling probably throughout primary – and some, as you are finding, need more teaching in phonics even in secondary.

I know of cases where children have exceptional ability to blend all-through-the-word for decoding and, in reverse, segment all-through-the-spoken-word for spelling – but a lack of knowing a comprehensive range of letter/s-sound correspondences maked these phonics skills basically redundant.

Add to that, teachers who believe in, teach or promote, multi-cueing reading strategies – and you have a disaster for some children. In such circumstances, the guessing becomes the dominant and default strategy – and, of course, the main phonics teaching comes to an end at the end of Year One – which is an issue you yourself have raised in your flowchart.

Many teachers think that phonics doesn’t ‘suit’ some children and this, too, weakens the resolve for phonics teaching. Regardless of the child/learner, it is the same alphabetic code and phonics skills that need to be taught and learnt and applied for long-term reading and spelling of new, longer and more challenging words.

Because of a history of ‘phonicsphobia’ in the teaching profession, phonics had to be introduced to teaching in an almost apologetic manner.

It is high time that phonics was given the place it truly deserves in our profession – which is the key to technical knowledge and skills for decoding and encoding – and this is something which is not ‘job done’ by the end of Year One – as you have found in your secondary teaching experience.

I do think, however, that if phonics was taught well in infants and in KS 2 for spelling, then it would no longer be of concern in secondary schools other than for pupils for whom English is a new language.

I tried to show with the graphic of ‘The Simple View of Schools’ Phonics Provision’ that there are widely different ideas of what phonics provision looks like from school to school. If teachers have a limited appreciation of what a content-rich phonics programme and practice consists of, then they will consider I’m crazy talking about continuing phonics beyond Year One – because ‘their’ version of phonics is so very limited and infant-like.

Great material

Josie – I’ve added you to IFERI’s list of bloggers here:

http://www.iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=6&t=487&p=655#p655

Debbie,

Thanks for letting me know. Very happy to be a part of that! Please do keep me connected. Still very much a strong advocate of SSP!

Thanks,

Josie