This is the 3rd blog post of a 6-post series on Metacognition. You can find post 1 here and post 2 here.

(If you’ve read the previous posts, skip straight to the key themes below. I’ll keep the intro the same at the top of each post.)

INTRO

In my recently-appointed role as a Lead Learner, I have been charged with delivering a series of six enquiry sessions for teachers on the theme of Metacognition*. Both a challenge and a privilege to lead such a great, diverse group of teachers with varying levels of experience and responsibility, I’ve been taking my research very seriously. (*For more information on our CPD Programme, designed by my colleague, Phil Stock, see his blog post here.)

aa

The sequence of posts I intend to write over the course of this year will 1. outline key areas addressed in sessions, 2. share questions that have arisen from our group discussions (sometimes as a result of the pre-reading that has been set), 3. offer points of interest from research studies that I continue to contemplate at each stage.

aa

I should make it clear from the outset – I have no doubt in my mind that metacognitive strategies can significantly enhance the learning of an individual, be they 5 or 95. With a grandparent of 89 who recently completed a BA degree in Humanities, I (and I know he does too) fully adhere to the notion that a high dose of metacognition and self-regulation can vastly improve the educational journey for a learner. It is the whos and whys and whens and hows that I believe need further thought.

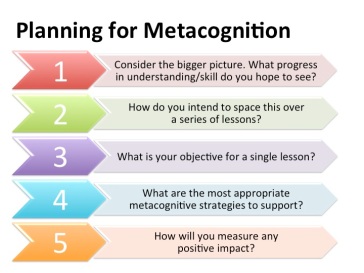

Prior to this session, teachers were asked to bring two items that would aid them during the planning time allocated within the session:

1. Their research and enquiry question* – these were written independently by teachers, who selected a very specific teaching element and target group to base their research on. Questions were devised in accordance with the guidance* shared with staff and agreed by line managers during appraisal meetings in the first half of the Autumn Term.

2. Any planning or knowledge of subject content due to be covered in the New Year.

*Screenshot taken from Phil’s post

aa

aa

8 themes from session 3:

- We addressed a query that arose in session 2

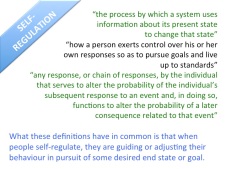

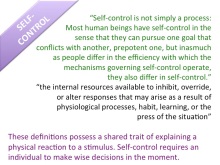

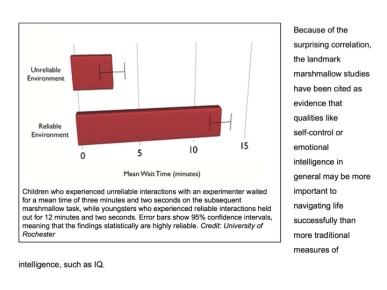

During one of the rich discussions we have shared as a group, a question was raised regarding the difference between two the concepts of ‘self-control’ and ‘self-regulation’. At the time, I admitted to not knowing what the research would suggest on this and could only speculate at possible answers. After some reading around this, I found the following quotes that served as a basis on which to summarise that:

Self-control: definitions seem to possess a shared trait of explaining a physical reaction to a stimulus. Self-control requires an individual to make wise decisions in the moment.

Self-regulation: definitions suggest that this concept helps an individual to guide or adjust their behaviour in pursuit of some desired end state or goal.

aa

It is worth mentioning that these two terms are also often used interchangeably, so it is not quite as black and white as it may initially seem.

2.We recalled key themes from session 2

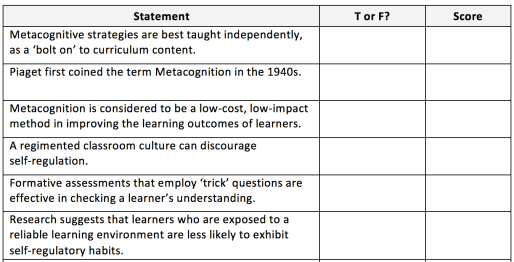

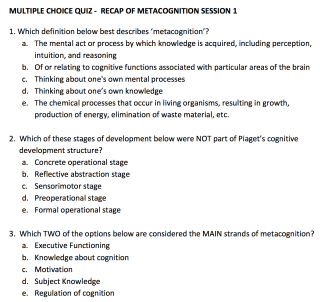

Once again, teachers were presented with a challenging multiple-choice quiz in order to familiarise themselves with themes from the first two sessions. These were completed independently, after which the answers were shared and discussed as a group. I should declare here that, despite the success of my first recap quiz used in session 2, I came under significant – though entirely civilised – attack from teachers present, for the phrasing of one or two of my questions.

In one section of the test, teachers had to judge statements to be true or false. For one of those statements I had written, “A regimented classroom culture can discourage self-regulation.”

Now, the response I had expected to receive was ‘true’, which was a little disconcerting when the choir of united voices before me replied ‘false’. This harmonious moment of unison soon became a cacophony when I overconfidently responded ‘WRONG!’.

In my mind, the word ‘regimented’ looked like a classroom of learners who lacked autonomy, conjuring visions of a teacher who was spoon-feeding curriculum content, denying students opportunities for deep thinking.

In the minds of everybody else, the word ‘regimented’ looked like a calm, orderly classroom.

It was evident where I had gone wrong and apologised without reserve. Needless to say that everybody scored a point for that question, irrespective of the answer they had given.

This was a fruitful learning experience for me, reminding me how careful one needs to be when constructing questions for formative assessments. A high quality test is critical if we hope it might reveal any valuable window of insight into the on-going learning processes of our students.

- We shared reflections on the pre-reading**

As has been the case in all three sessions so far, teachers were brilliantly forthcoming in sharing their personal reflections on the reading we have engaged in. Conscious of time constraints on this session (mindful of reserving time for planning), we didn’t spend huge amounts of time dwelling on this though, again, some very interesting points arose. Two comments of note included:

a) The video talk by Dr Derek Cabrera greatly helped in provoking one to think about the value we place on thinking in our lessons. It leads us to question whether the pedagogical approaches we employ to share information about our subjects are the right ones.

b) Reference was given to a concept discussed in John Hattie’s chapter on self-control, called ‘ego depletion’. Many studies, including the work of psychologists such as Roy Baumeister et al (1998), propose that, “Self-control is a finite resource that determines capacity for effortful control over dominant responses and, once expended, leads to impaired self-control task performance, known as ego depletion.”

Teachers discussed the implications of this concept in relation to the demands we put on our students in a variety of learning situations.

**Pre-reading list focus:

Dr Derek Cabrera, How Thinking Works (online video clip)

John Hattie, Visible Learning and the Science of How we Learn

Chapter 26, Achieving Self-Control

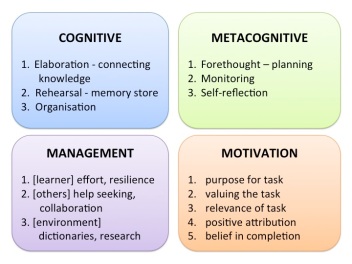

- We took a shallow dip into the field of Executive Function

In response to a dialogue that arose in session 1, a brief amount of time was spent considering the concept of Executive Function. An overview video from Harvard was shown, outlining the premise that EF is, in essence, the CEO of all cognitive processes. According to Harvard,

“Executive function and self-regulation skills are the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully. Just as an air traffic control system at a busy airport safely manages the arrivals and departures of many aircraft on multiple runways, the brain needs this skill set to filter distractions, prioritize tasks, set and achieve goals, and control impulses.”

We are taught that EF skills depend on three types of brain function:

- working memory

- mental flexibility

- self-control

- We attempted a task that challenged our Executive Function ability

To understand the demands our EF skills are consistently required to monitor, we looked to the unfaltering wisdom of the Two Ronnies. While not technically qualified as cognitive psychologists, these men have been pioneers in broadcasting the complexities of EF. Watch their informative Mastermind sketch here.

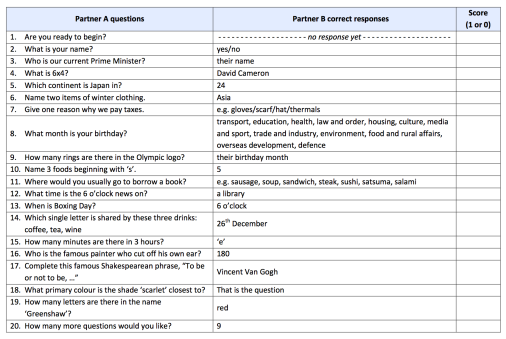

Following this, teachers were challenged to attempt the same task in pairs, responding with an answer to the previous question instead of the current one. Here is one of the two sheets I devised to test teachers’ mental flexibility.

After a few hot minutes of serious brain activity (and much laughter), we reviewed how the task had gone. The two main comments that arose were:

1. It was more difficult to ask the questions, since your brain is having to read, listen, look ahead and score at the same time.

2. It was much more difficult to answer when you had to complete an operation in order to reach an answer, while also storing the next question in your mind.

One teacher raised a concern that this could have a significant negative effect on our learners. A student might easily fail to cling on to an influx of information we have given, if we have not considered the demands we are placing on their working memory at any one time.

6.We made associations between our questions and the Metacognition session content

As mentioned in the intro of this post, staff referred back to their individual research and enquiry questions, making connections between these and the content we have covered so far in sessions. This was a brief discussion, before moving into more tailored groupings for effective planning and preparation time.

7. We regrouped according to enquiry question focus and began planning

Prior to this session, I had spent time reminding myself of teachers’ enquiry questions and carefully grouped them according to the focus of their upcoming trial (not necessarily by department). These were broadly grouped around themes including: self-assessment or self-monitoring, applying technical or higher level vocabulary to work, social or emotional attitudes to learning, ability to apply strategies taught. This list is not exhaustive but incorporates many of the key focuses shared by teachers in our group.

In these subgroups, teachers discussed their hoped student outcomes as a result of new strategies they will seek to implement in the New Year. They also identified relevant strategies from a menu I had collated to best suit their subject area and enquiry focus. Strategies were selected from a range of research studies and articles I’d read in preparation for these sessions, including a reference table outlining many of the great techniques explored in Doug Lemov‘s book ‘Teach Like a Champion 2.0‘.

8. We looked ahead to January, considering how to monitor any progress

While a six-week period is a short time in which to measure improvement in the deeper learning of students, we will intend to pause and consider how the trial is going in February. Teachers were informed that, when we meet on February 10th, it would be great to hear from each member of the group:

a) what strategies have been implemented

b) what has / has not worked so well and

c) what improvements to learning, if any, have been noticed in that time

aa

Any evidence can be simply anecdotal, video footage, photo evidence, student work, formative assessment, student interviews or surveys etc. It is left to the teacher to make the best decision as to how to measure any change, though it was advised that some form of pre and post comparison might be useful. The trial will continue for the remainder of the year, though this next session will serve as a good review point along the journey to reflect and revise the metacognitive approaches employed.

aa

Following the session, I shared a step-by-step timeline of actions that need to take place between now and February. This includes arrangements for planning, delivery and reviewing. I will also be sharing any reading I find that links to teachers’ questions in the interim period, as well as being available for on-going support.

aa

I’m geekily eager to see how the next phase goes.